Short bowel syndrome (SBS) is a rare condition that affects about 3-4 people per 1 million every year. It develops when a large part of the small intestine is either missing, surgically removed, or dysfunctional.

The syndrome occurs when a person loses more than 50% of their intestinal length or there is less than 200 cm of a functional small intestine left.

Keep in mind that not all people who have lost a significant amount of small intestine develop a short-bowel syndrome. Its occurrence and severity depend on the exact segment lost, your age, and the segment size compared to the total intestinal length.

SBS leads to poor absorption of nutrients and debilitating symptoms. Related complications include cachexia, stomach ulcers, kidney stones, and bacterial overgrowth in the gut.

In adults, SBS can sometimes be prevented by using more sparing surgical techniques. Yet, there is no known prevention against congenital short bowel syndrome.

How and why does SBS occur?

According to the National Institute of Health (NIH), the most common causes of short bowel syndrome are diseases that require surgical removal of parts of the intestines.

Usually, these are life-threatening conditions that require timely surgical intervention.

Even without surgical resection, the damage or injury to the small intestine caused by these diseases is so significant that it will lead to malabsorption and SBS. Examples of such conditions in adults include:

- cancer or cancer treatment

- autoimmune conditions (e.g. Crohn’s)

- traumas

- loss of blood flow to the intestine

- intestinal blockage (i.e. ileus)

Short bowel syndrome may vary from mild to severe. Studies reveal that mortality in adults ranges between 15% and 47% depending on age, severity, and comorbidities.

After the resection, every patient goes through a series of physiological changes as a part of the adaptation of the intestines. The process involves 3 phases – the acute phase, the adaptation phase, and the maintenance phase.

The acute phase starts immediately after the resection and may last 3-4 months. During this phase, the absorption ability of the intestine is highly reduced and there is a high risk for dehydration, electrolyte loss, malnourishment, and deficiencies. Water loss may reach up to 8 liters per day.

The adaptation phase starts 48-72 hours after the surgery. It occurs due to the ability of the small intestine to compensate for the resected parts by a process called intestinal adaptation.

The process continues for up to 2 years in adults. During the process, the intestine can dilate and lengthen thanks to increased cell production. The mucosal lining also adapts to increase the absorptive area of the intestine.

The maintenance phase occurs after the end of the adaptation phase. During that stage, the absorptive capacity of the remaining intestine has reached a maximum. Depending on the degree of recovery, the patient may be able to eat normally or remain under nutritional support.

In infants, SBS may occur due to a birth defect (congenital) or necrotizing enterocolitis (NE). NE is a condition with unknown etiology which mostly affects preterm babies. The mortality in infants with SBS is significantly lower.

Besides, the effects of intestinal adaptation in children are influenced by their growth and development. Therefore the process continues for more than 2 years and appears to be more effective than in adults.

That’s likely due to the higher levels of various growth factors in children, such as human growth hormone (HGH) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), as well as their higher adaptational abilities.

Signs and symptoms of SBS

SBS reduces the ability of the digestive system to absorb energy and nutrients from the food you eat. This leads to malnutrition, deficiencies, and gastrointestinal symptoms.

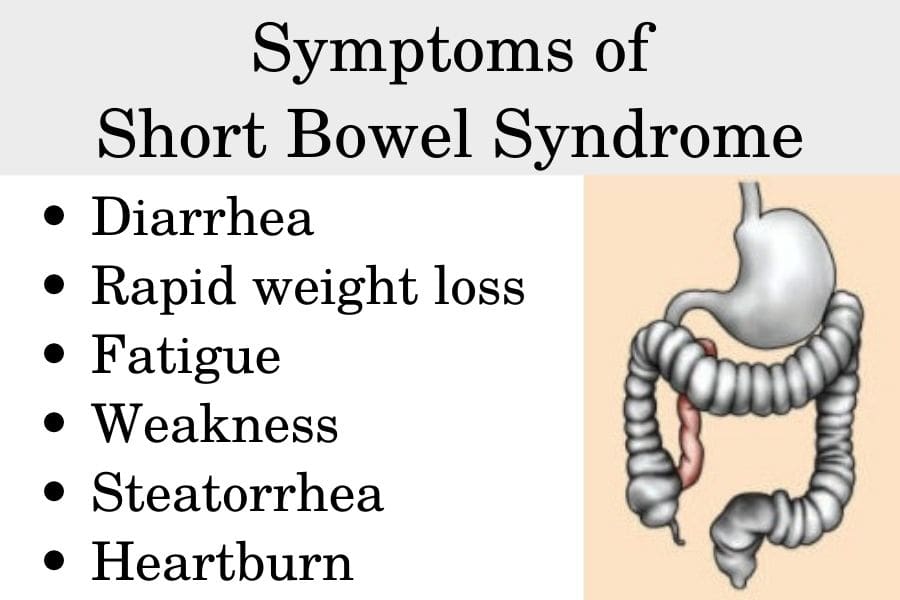

One of the most common symptoms is frequent, watery stools. Diarrhea in short bowel syndrome occurs because there are many unabsorbed osmotically active nutrients that draw water into the intestines.

The symptom is worse if parts of the large intestine are also missing and it may lead to serious dehydration. Severe and rapid dehydration can be life-threatening.

In SBS the body is deprived of nutrients, energy, and water. This leads to symptoms such as rapid weight loss, fatigue, and weakness. Furthermore, the protein deficiency that develops as well may cause edemas, predominantly in the lower limbs.

Apart from dehydration, malnourishment is the most serious symptom. It may progress into severe wasting called cachexia which is life-threatening without proper treatment.

Moreover, SBS leads to severe malabsorption of dietary lipids which results in high levels of fats in the feces. The symptom is called steatorrhea and its main signs include loose and foul-smelling stools due to the unabsorbed lipids.

One of the factors which determine the severity of the different symptoms and the type of deficiencies is which part of the small intestine is missing or dysfunctional.

If the first or the middle part of your small intestine is resected or dysfunctional, then you may experience heartburn. Those segments produce inhibitory hormones that regulate normal stomach acid production. If they are missing it leads to hyperacidity, reflux and an increased risk of peptic ulcers.

Furthermore, experiments report that the majority of nutrients are absorbed in the middle part of the small intestine, while the last part called the ileum absorbs mainly bile acids and vitamin B12.

Yet, the ileum has higher adaptive capabilities and if the rest of the intestine is removed, the ileum may be able to take over its function. On the other hand, other parts such as the jejunum (middle intestine) have significantly lower adaptational capabilities.

How to diagnose short bowel syndrome

Only a medical doctor can diagnose you with short bowel syndrome. The diagnostic process includes:

- medical history

- physical exam

- laboratory tests

- image diagnostics

Your doctor will begin by taking your medical history. The process includes asking you questions about your symptoms, chronic conditions, and whether you have previously undergone any surgeries.

Then your physician will assign you laboratory tests such as taking blood and stool samples. Drawing blood from your vein will provide information about the levels of vitamins, minerals, proteins, and blood cells in your body.

The stool sample test will reveal whether or not you have steatorrhea or other signs that indicate malabsorption.

In addition, you may undergo imaging diagnostics such as an X-ray or CT scan, which help evaluate the condition of your intestines and locate obstructions, dilatations, or other potential problems.

The procedure often involves ingesting a contrast that helps the doctor better assess the health and function of your intestines.

Main treatment options for SBS in adults

Mild forms of short bowel syndrome are treated via a combination of medications and dietary changes.

Most of the medications are symptom-specific, such as anti-diarrheal (loperamide, bile-acid binders, digestive enzymes) and antacids. Besides, antibiotics may be used in cases of bacterial overgrowth.

Medications that increase intestinal absorption in SBS include teduglutide and HGH

Teduglutide is an injectable medication that aims at improving adaptation. It works by promoting mucosal growth and possibly slowing down gastric emptying.

The human growth hormone also promotes mucosal growth, improves intestinal absorption, and speeds up adaptation. HGH is often coupled with oral supplementation with the amino acid glutamine, which is the main “food” for the cells in the intestinal mucosa.

In addition to medications and diet, moderate forms of SBS may require periods of nutritional support. Nutritional support involves parenteral feeding which delivers fluids, electrolytes, and other nutrients directly into your bloodstream via a venous catheter.

Severe forms require long-term parenteral nutrition and oral rehydration therapy, in combination with medications and dietary changes. Even though the patient may not absorb the food they ingest, normal eating stimulates the intestinal adaptation process.

Surgery may be applied to lengthen the small intestine in severe SBS and slow down the passage of the food in order to improve its ability to absorb nutrients.

In addition, severe SBS can be treated with intestinal transplantation. This requires a living or recently deceased donor who is compatible with the patient. The majority of transplantations are performed in pediatric patients.

The survival rate after prolonged parenteral nutrition is comparable to that after intestinal transplantation.

Nevertheless, surgery or intestinal transplantation may lower a patient’s dependence on parenteral feeding and reduce treatment costs.

Studies report that long-term parenteral nutrition leads to cholestasis which increases the risk of liver disease and gallbladder stones. The risk can be reduced with the addition of choleretic medications.

How Zorbtive treatment helps adults with short bowel syndrome

Zorbtive is currently the only FDA-approved brand of HGH for the therapy of short bowel syndrome. The treatment is available only in adults with SBS since its safety and effectiveness in children are not studied yet.

Zorbtive comes in 8.8mg vials. Inside, the HGH is in powder form and requires reconstitution with 1-2 ml bacteriostatic or sterile water before use. Once reconstituted into liquid, the medication must be injected subcutaneously to be effective.

Standard Zorbtive dosage is 0.1 mg per kg of body weight with a maximum of 8 mg per day. You can take it for up to 4 weeks and then continue the therapy with 50% of the original dose.

If there are any side effects, your doctor will reduce the dosage by 50%. If adverse reactions persist then HGH may be discontinued.

Read more about how much HGH to take and how to avoid adverse effects while achieving your treatment goals.

The most common side effects include water retention and reduced insulin sensitivity. Signs of water retention include edemas, carpal tunnel syndrome, and joint pain.

Usually, these adverse reactions are transitory and Zorbtive is well-known for its favorable safety profile. Contraindications against the therapy include active malignancy and known hypersensitivity to HGH preparations.

Studies reveal that HGH can effectively increase the absorption of energy and nutrients in SBS patients

Furthermore, trials report that 4 weeks of growth hormone therapy reduces the need for parenteral nutrition and the benefits are sustained for at least 3 months.

Thanks to its anabolic effects, HGH therapy also helps increase body weight and lean body mass in SBS patients.

Diet recommendations

There are specific dietary recommendations for patients with SBS. They should be followed throughout the whole treatment process and in some cases – indefinitely.

If you have short bowel syndrome, you should focus on consuming smaller food portions per meal but more frequently. It’s recommended to eat 6-8 times every day.

Eating smaller amounts of food per meal slows down the motility of your gastrointestinal system and gives more time for nutrient absorption.

Furthermore, high-fat foods may lead to steatorrhea and worsen your symptoms. Therefore, you should replace them with low to moderate-fat options.

All foods that may cause diarrhea should be avoided as well. This includes foods high in fiber, sugar, or sweeteners. This is why you may have to replace whole-grain options with refined-grain foods.

Lactose intolerance is also more common amongst patients with SBS so you may have to avoid dairy products and take calcium supplements instead to prevent deficiencies.

In addition to normal or parenteral nutrition, you may also need to take supplements containing vitamins. Usually, those include fat-soluble vitamins such as vitamins A, D, E, and K.

They are often deficient due to the poor absorption of fats in SBS patients. Therefore it is recommended to supplement with water-miscible forms of these vitamins.

In addition, you may need B12 injections if the resected part of your small intestine includes the ileum.

Get a free consultation with our medical expert for any questions about hormone replacement therapy